The muted majority

Users who can’t even find the microphone to tell you what’s wrong

I feel like I’m always hearing the same few things in every meeting:

- “If we just leverage AI into our existing product…”

- “We’re looking for a feature to increase growth by 5% next quarter…”

- “I… I can’t hear you. I think you’re on mute.”

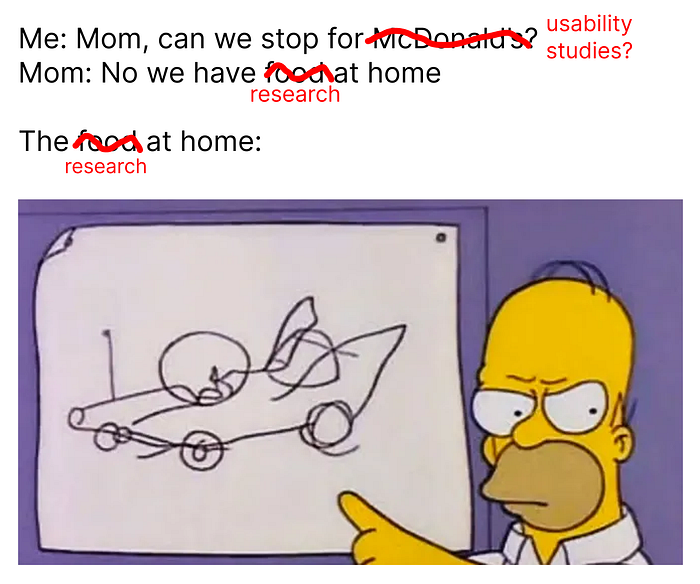

Living in the present is pretty cool. We’re surrounded by technology that even ten years ago seemed impossible. Our software is smarter. More decisions are made behind magic curtains. Cars can drive themselves. We voice-command our home appliances. But we also need screens to make our cars drive, apps to turn down the air conditioner, and a stable internet connection to update our fridge’s firmware. New technology isn’t always easier to use, and despite all of these achievements, we still wade awkwardly through virtual meetings because we can’t nail down how exactly to make the controls intuitive. Somewhere along the way, designers lost sight of their responsibility to make products usable. We started chasing new features before ensuring that they were useful features. And we stopped soliciting feedback from users who need their voices heard the most.

If you’re not in a heavily research-driven organization, it might be easy to nod along with product requirements when they confirm your biases. Confirmation bias is dangerous. If you’re reading this piece, there’s a good chance you’re ahead of the curve on tech adoption. If your work involves software at all, you’re probably above average in terms of tech proficiency. There are a lot of people in this world and if you’re not careful to leave your tech-centered bubble once in a while, you might forget how few of them know how to attach a file to an email. Even human-centered designers — professionals of social anthropology — often get deceived by our own selection biases. So it’s no surprise that we often find ourselves motivated to make more technology rather than improve technology.

A jury of one’s peers

“OMG, I haven’t had this many ‘you’re on mute’ calls since the beginning of the pandemic,” a friend texts me after being dismissed from jury duty via Zoom. “A jury of your peers unfortunately does not mean your tech-savvy peers.”

My friend is more right than she even realizes. I don’t often consider the similarities between UX researchers and trial lawyers, but it turns out both are on an eternal quest to characterize the “average” person. And at the risk of offending my own peers, I think the lawyers might actually be better at it. Assuming that the court system fulfills its goal of assembling a true cross-section of society for the jury selection process, it’s no surprise that the average participant on that call would be less proficient with a computer than the groups we work with in the tech industry. (Full disclosure: I work on a video call product team; there’s no escaping that familiarity bias in my own daily life.)

But those below-average proficiency users are real people. And they’re people who are expected to use technology, even if rarely. They’re projecting background noise when they shouldn’t be. They’re inaudible when you need to hear them. And they definitely don’t know how to pair Bluetooth earbuds ever since you took their perfectly fine headphone jacks away. By definition, they’re only half of this group, but they’re ruining the experience for everyone. And it’s not their fault.

The voices that go unheard

No matter what product we work on, we’re always seeking user input. But we often get caught up in the “user” element: chasing people who already use the product, people we expect to use the product, and — to capture beginner usability issues — people who might consider using the product in the future. But no matter how hard user researchers try to get an even balance of everyday people into a usability study, there’s bound to be selection bias.

Researchers may screen for participants who use a variety of browsers, but how many people are they letting through who don’t know what a browser is? What about people who claim they’ve never heard of your product even if they just finished using your product? People reluctantly making a video call aren’t volunteering to share their thoughts after they exit. The people most likely to struggle using your product are the least likely to make it into the usability study.

Even among more familiar users, usability studies often take a back seat to requirements-gathering exercises. When large design organizations are driven by a product team, research priorities can become focused on validating product ideas and features rather than listening to what users actually want or need.

This isn’t a unique problem, and it’s not the fault of product teams or research teams or design teams. It’s the result of businesses operating like a business and seeking out a moonshot product that will make a splash in a press release. I can’t blame them; nobody watching a public product launch is salivating over the news that “we’re moving the most common action buttons to where more people expected them.”

Missing the forest for the trees

“It’s hard to do simple stuff.”

I recently participated in a design workshop where we took a deeper than usual dive into user feedback. Among the feedback were dozens of comments that users found it difficult to do seemingly simple things. While reading all of these comments, it was easy to empathize with these frustrated users. We built a product that can do many things. We built it around personas who have many tasks they need to accomplish and made sure that all of those tasks can be done. But what we hadn’t considered was that many of the users who left these comments seem to have a narrower range of tasks when they use the product. They’re here throughout the day to perform one action many times, and each time, they have to navigate through all of those other things first. And looking at the product from their perspective, I can see how it is indeed hard to do simple stuff.

In hindsight, this isn’t much of a revelation. So many products make it hard to do simple stuff. And most products that are easy for one person probably leave another person feeling that difficulty. The point is that if more product teams keep an ear to the ground, they will probably receive the same feedback. It just doesn’t always float to the top.

The moonshot not heard ‘round the world

“What excites you the most about AI? What’s your opinion on LLMs? What’s your favorite technology trend of 2023?”

Those are all real icebreaker questions I’ve been asked by other designers in the last few months. I want to have a cool, optimistic answer. I think they’re expecting me to. But every time I see a new hype train boarding eager passengers, it feels like we’re grasping at ideas we don’t fully understand yet rather than addressing the concrete usability issues we still have at ground level.

Sometimes I’m a curmudgeon when it comes to adopting new trends, technology, and design paradigms. (Okay, it’s a lot of the time). I know there are a lot of cool things we can do with AI, with large language models, with automation and algorithm-driven customization. But those are just new things we can do with technology, and there will always be new things we can do with technology. What actually excites me about designing technology is that our job is never done. We have enough opportunities to make things better without even chasing the newest thing. If you really want to break the ice with me, ask me what technology I recently encountered that felt unnecessary, or what simple problem seems really hard to fix.

We designers have our work cut out for us. If this all sounded like a pessimistic anti-technology rant, I apologize, because I actually see a lot of opportunity ahead of us. The lesson here is that the people who have the most trouble using your product are the least likely to tell you so. Along with every other piece of user feedback you collect, you should assume that there are more people who find “the simple stuff” hard to use. Amplify that kind of feedback when you see it. Don’t wait for a ton of users to tell you.

If I have my own reservations about inserting AI into everything, I can only imagine the feelings of anyone who already feels overwhelmed by our current technology. I think about people for whom technology is a tool, not a hobby. I think about all of the technology I passively encounter on a daily basis that doesn’t work well, and how few of those problems can be solved by automation. I think about my parents, who are rarely using the latest technology and don’t seem all that invested in chasing it, and who only recently got comfortable navigating through a video call. I’m just happy they finally found the mute button.